Path Tracking: Pure Pursuit

NOTE: This chapter makes significant use of resources from this article, adapted for use in TinyKart. Please take a look there for more details on the math side of things.

Now that we have a target point, all you need to do is find out how to actually get the kart there. This is the responsibility of path trackers.

Much like path planners, path trackers come in many varieties, depending on the robot and requirements. For example, some planners like Pure Pursuit simply directly head to the target, some like ROS's DWB attempt to avoid obstacles, and some use advanced control algorithms such as Model Predictive Control to attempt to also handle vehicle dynamics (such as wheel slip). These range in difficulty of implementation from elementary to reasurch.

In the last chapter, you were using a reference implementation of pure pursuit. In this chapter, you will learn how to reimplement this yourself, and get a better idea of how to tune it.

Kinematics

Before we can talk about pure pursuit, we first need to introduce vehicle kinematics. Kinematics is the study of how things move without respect to forces (dynamics). For example, the kinematics of a car define where the car will go given some steering angle input alone, without considering things like wheel slip that depends on surface friction. While far less accurate than using dynamics, robot kinematics gives us a good estimation of how our robot should move given some command.

Because kinematics doesn't depend on forces, it could be said that it instead relies on geometries. This means that the physical layout of the robot defines your robot's kinematics. While these are theoretically infinite, they tend to come in only a few varieties:

Differential Drive:

Skid Steer:

Omnidirectional:

And of course...

Ackermann:

Ackermann Kinematics

Because cars use ackermann steering (as any other mechanism would fail at speed), we will only discuss ackermann kinematics in detail. Conveniently, the kart also uses ackermann steering so all of these equations apply to your real work.

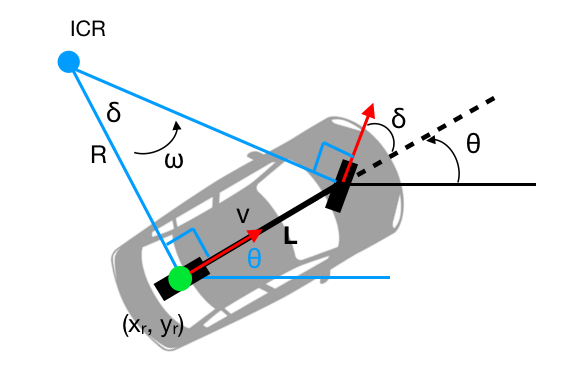

While one could model vehicle kinematics using all four wheels, it's common to simplify them down even further to just two - the bicycle model:

At this level of simplification, things should be pretty clear. To break it down:

- \( \delta \): The angle of our front wheel. In actuality, this is the average of your two front wheels. Note that because of the right triangle formed by the wheels, the angle of the ICR is actually the same as our front wheel, which we can exploit.

- R: The radius of the circle our rear axel is following, aka the current turning radius. This is the single thing that identifies the path we will follow.

- L: Wheelbase, only useful as the opposite side of the right triangle.

Some things to note:

- The vehicle turns about its rear axle, so we consider the position of the rear axel the position of the robot.

- L is constant, so either \( \delta \) is chosen to find some R, or R is chosen to achieve some \( \delta \).

- Using this model, robot motion must always occur in arcs.

- There is a minimum turning radius a vehicle can make, governed by its wheelbase.

- Velocity does not change turning radius, but it does change if you will slip while making that turn.

Pure Pursuit

With that model in mind, we can now introduce pure pursuit. Pure pursuit is a path tracker that computes the command to reach some target point by simply calculating the arc to that target point, and heading directly towards it. With this in mind, it's clear why Ackermann kinematics are useful, as they give us a means to find a steering angle given an arc.

Pure pursuit is a tad more than that, however. It's main trinket is lookahead distance. Basically, PP will only calculate arcs to points so far away from itself, in order to strike a balance between making sudden turns and slow turns. You can think of lookahead distance as a tunable parameter that sets the "aggressiveness" of the karts steering.

Let's go through a pure pursuit iteration step by step.

Enforce lookahead

When using a path with multiple points, the first step would be to find the intersection of the lookahead distance and the path, in order to find the target point. For TinyKart we already have the target point, so this step isn't needed. However, we still need to include the lookahead distance somehow, else pure pursuit will turn far too slowly.

To do this, we simply do the following:

- if dist(target) > lookahead

- set target point to lookahead distance, while preserving the same angle. This can be done easily with some trig.

- else, target is within lookahead, so just use target.

Calculate arc to target

To calculate the arc we need to follow to reach the target point (which remember, is given by R), we can exploit the geometry of the problem.

To find R, and thus the arc, we can use the law of sines in the geometry above to derive:

\[ R = {distinceToTarget \over 2\sin(\alpha)} \]

Calculate steering angle for arc

Finally, we need to calculate the steering angle required to take the arc described by R.

By the bike model discussed prior, you can see that the steering angle relates to R by: \[ \delta = \arctan({L \over{R}}) \]

By substituting R for our arc found in the last step, we can solve the equation to find the required steering angle \( \delta \).

Now that we have our steering angle, which is our command, pure pursuit is complete.

Visual

For a visual representation of pure pursuit in action, take a look at our pure pursuit implementation for Phoenix:

Tuning

Before I hand things off to you, I want to give a brief overview of tuning pure pursuit, since there isn't much media on it.

As mentioned before, lookahead is the main parameter for pure pursuit. For TinyKart, it directly controls the aggressiveness of a turn, since we drag target points closer to the kart, rather than sampling a closer point on a path. Because of this, a closer lookahead distance will always lead to a more aggressive turing angle, so long as the target point is farther than the lookahead distance.

Because of this, tuning lookahead on tinykart is rather simple, if tedious:

- If the kart is moving its wheels too little and hitting the outside of turns, lower the lookahead distance

- If the kart is moving its wheels too dramatically and hitting things as a result, raise the lookahead distance

Generally speaking, a larger lookahead distance should be faster, since turning causes the kart to lose speed from friction.

Your turn

It's finally time for your last assignment! Of course, this will have you writing and tuning your own pure pursuit. Build this off of your code from the last chapter.

Find this line in your loop:

auto command = pure_pursuit::calculate_command_to_point(tinyKart, target_pt, 1.0);

And replace it with:

auto command = calculate_command_to_point(tinyKart, target_pt, 1.0);

Then somewhere in your main.cpp, add:

/// Calculates the command to move the kart to some target point.

AckermannCommand calculate_command_to_point(const TinyKart *tinyKart, ScanPoint target_point,

float max_lookahead) {

//TODO

}

Implement pure pursuit in this function, and test it our with your existing code.

As a bit of an extra, consider using your past work from chapter 4 to set the throttle component of the command proportionally to the distance to the objects in front of the kart.

Good Luck!